There’s one game I find myself getting back to every few years, over and over again, and that’s The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. It’s also a popular topic of discussion, inspiration and reminiscence among friends of mine - a shared experience to touch upon every now and then, each having their own favorite parts of it. It definitly has achieve a sort of cult-status, but what exactly makes it such an enduring classic? And is it really better than its sequels? This is what I’d like to explore in this blogpost.

Cliffracers eradicated in my most recent playthrough: 201

A Word on Problems

I’d like to start by recognizing that the game has problems. Although I’m a huge fanboy, I try to be critical of things. Nothing is more annoying than someone not being able to contextualize their object of adoration.

First of all there is the obvious problem of age. The game came out in 2002 so it’s obviously limited by the technology of its time. The modding community has done wonders with it though and solved quite a few of its limitations in graphics and a lot of the latent bugs have been fixed by the community.

The biggest problem, to new players or maybe even in general, is probably the combat system. It’s actually quite a standard implementation of dice-based mechanics from tabletop rpg’s, but it doesn’t work well with the first person combat that the game presents you with. It exists in between both those worlds and is therefore a bit uncanny. This is rectified in later iterations of The Elder Scrolls games.

Some people don’t like the dialogue system in the game, but I beg to differ. The text-and-hyperlink-based system lowers the entry-level for mods (no need for professional voice-actors or expensive audio equipment) without breaking immersion. The hyperlink system offers a way to delve into the lore as deep as you want to. This system does break down a bit when using the journal, where everything gets muddled because of this. Even the addition of an quest-index did only a little to alleviate this.

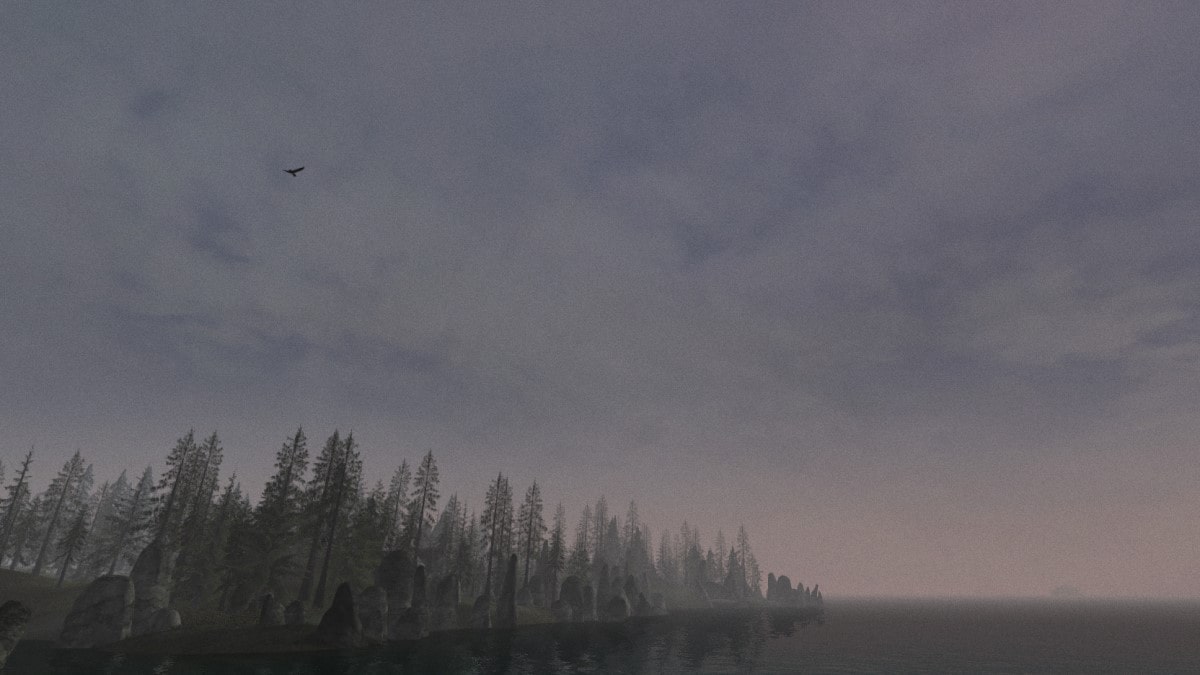

A last limitation is that of the technology. Released in 2002, the game engine is dated and has its constraints. Graphically the game’s textures are smudgy and effects are lacking, the island shrouded in a weird fog that limits your view distance (which one friend of mine thinks adds to the mystery of the island, so to view this as a deficiency is rather subjective). Quite a lot of these shortcomings can ben rectified by mods. There are loads of them, and also third-party programs and add-ons for managing and expanding the games possibilities. Community code patches fix lots of problems, tweak a lot of issues for a more enjoyable experience and add new possibilities for other mods. And then there are the huge Morrowind Graphics Extender XE (that adds loads of graphic options, such as rendering distant lands and adding shaders), Tamriel Rebuilt (reconstructiong all of the Morrowind province) and OpenMW (building a whole new engine for the game). These are not only what makes the game great, but are also proof of the quality of the original itself.

The World of Vvardenfell

More than the other The Elder Scrolls gmes, the island of Vvardenfell feels really alien. It’s filled with wonderfully unique fauna, such as nixhounds, guars (both wild and tamed pack-animals) and the scourge of the cliffracers, or the floating jellyfish like netches, the mudcrabs and the staple of the local economy: the kwama that breed in underground lairs that function as ‘egg-mines’. The only generic animals native to the land are rats. And I haven’t mentioned the myriad of other creatures that can be encountered in dungeons, temples, ruins or caves everywhere, that dot the landscape.

The flora too is unique. Most recognizable are the giant mushrooms that grow in multiple regions instead of trees. The House Telvanni wizards even made their dwellings in magically grown ones, giving their cities an organic and confusing feel to them. But lots of other plants are important, culturally as foodstaples or as alchemical ingredients. Giant sponges, bulbous roots, saltrice, ash yams, all kinds of flowers and weeds, are all original and have their own set of properties.

The landscaping too is something that deserves admiration: the island, dominated by its large volcano, isn’t actually all that big (around half of Oblivion and Skyrim), but it does feel huge by smart placement of obstacles, landmarks and travel options. There is no fast-travel options, except for payed-for transportation by boat and siltstrider (oh, did I mention giant fleas that are used as caravan transports?) or teleportation to fixed points such as temples and mages guilds, and only around half the island is quickly accessible through any of these means. The Ashlands, one of the hundred little islets of Azura’s Coast, the inner Grazelands or the desolate Molag Amur volcanic pits require the player to at least travel there on foot from a distant outpost. While this was primarily a smart way to make the most of the limited viewing distance to create a sense of distance and space, it’s a testament of its ingenuity that it holds up very well with the MGE XE distant lands generated. The added visual fidelity never did away with the necessity of following vague directions and roadsigns to get to where you want to be. It makes it a litter easier maybe, by being able to orient yourself with some distant daedric ruins for instance, but it never spoils the search.

Besides that, it also feels like a believable place: the differences in between regions are carefully balanced with its similarities. Red Mountain provides a grateful justification for this: whole parts of the land are influenced by it: foyadas (‘fire rivers’) cutting through the landscape, lands filled with volcanic activity and covered in ash. These contrast nicely with the more lush and habitable regions such as the swamplike Bitter Coast, the verdant Ascadian Isles or the rocky Zafirbel Bay, dotted with many islands, both inhabited as barren, and rocks jutting out of the sea.

This 2020 playthrough was also one of the first times really exploring the larger landmass created by the Tamriel Rebuilt project. Large parts are little more than empty places to wander through, with almost no npc’s, let alone any content in the name of quests or interiors. But this alone is already a triumph of the community and shows of some of the originality in landscaping that is possible and often with more attention for the distant-land look.

Culture and Design

The alienness extends beyond just the geography, fauna and flora. Arguably more important is the strange Dunmer culture you end up in as an outsider. Isolationist and unwelcoming, it’s not the first thing you’d expect of a fantasy world. But this closed-off society itself isn’t monolithic; there are competing political cliques and houses, commercial interests that clash, old folkloristic clans that hold different traditions sacred and subversive sects. Luckily, for a newcomer, there’s the more welcoming, comspolitan Imperial outposts and forts - although in slow decline.

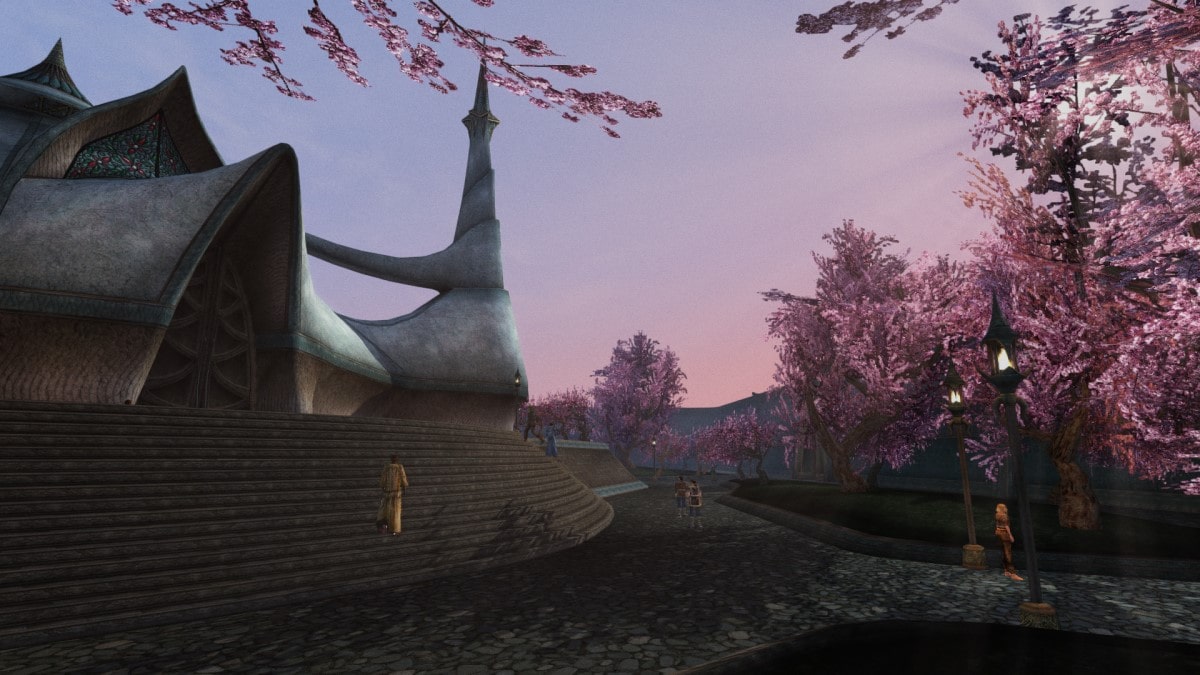

One of the most important design elements is the wildly varying but distinct Dunmer architecture. While the ‘savage’ nomadic Ashlander tribes live in yurts, the settled Dunmer of the Great Houses live in permanent structures: there are plantations, towns, temples and cities to be found, and the style depends on the ruling elite. But all of these are decendants from the Velothi style, that was taught by the daedric prince Boethiah. All of them use common elements and materials in their structures, namely the loam used and the rather organic appearance of the shapes, even for the rather rectangular Hlaalu structures. The Temple architecture of Vivec resonates in the smaller temples with their cupolas and tunnel-like interiors. The Redoran incorporate insect and crab-like forms and motifs (and even a huge crab-shell as the exterior of their council house). The only ones really diverging from the Velothi pattern are the Telvanni wizards who build magical plant towers and likewise styled town around them, where access is limited by a users lack of magical ability, since levitation is a necessary skill to reach the upper reaches of the towers and power.

Besides the cities themselves, there are other structures of interest spread around the world. The many tombs are in the same Velothi style for the settled houses, build into the ground. The ancient and lost Dunmer strongholds look a bit like Mayan buildings, made of boulders and on an elevated platform, and emanate a terror that’s warranted, since these are often filled with danger. This is in contrast to the underground Dwemer fortresses, filled with angular furniture, steam pipes and some sort of magical-electric lighting - testament to their rational-scientific nature. And last, but not least, the daedric shrines have their own twisted architecture: angular, madness-inducing spires and vaults, betraying no certain origin of their style, with spiked incense-burners hanging from the ceiling, belching greyish smoke, these places are always interesting yet fraught with many dangers.

It’s telling that the least original elements are those that are actually from outside of Morrowind and Dunmer culture proper: Empire architecture is based on the Roman styles and Nord elements are medieval and viking influence. These are the two most direct neighbours, geographically speaking, so elements of these can be found in many places. But these are rather new additions to the landscape and obviously foreign.

There’s also a highly diverse set of enemies you’ll encounter, besides the general fauna of the world. The least original of which are the undead; skeletons are standard fare for fantasy games, but the twisted bone walkers are vile and dread-inducing. Ghosts are also common, which makes sense considering the central role that ancestor worship plays in ancient Dunmer culture, even skirting the edges of necromancy. There’s also the diverse daedra - beings summoned from other planes of existence - that don’t look alike and haunt the old shrines en get summoned by oftentimes mad cultists. The underground fortresses of the Dwemer were left functioning after their sudden disappearance, with their constructs - spidery robots and steam machines - still running. Because of the fact that a lot of these ruins are situated on Red Mountain, these are often inhabited by the disciples and henchmen of Dagoth Ur: ash vampires and their kin, dunmer mutated beyond recognition by the ‘divine’ corprus disease, mentally twisted by dream-visions.

As regards to weapons and armor: the most interesting, native designs such as chitin and bonemold weapons and armour, are evocative and inspiring. The closed helmets that are suited for life and survival in harsh conditions in the ashlands and are sourced from local resources such as giant insects are very much in keeping up with the allround theme. Unfortunately these are mostly low-level items, quickly overclassed by the more powerfull orcish, glass, ebony or daedric sets, that are mostly clunky, garish and a little bit too edgy (both literally and figuratively) in their design. There’s almost no reason to stick for a longer time to those more cultural appropriate outfits.

Lore and prophecy

One of the most interesting aspects of Morrowind, in my opinion, is the way that it deals with its main storyline. In most singleplayer roleplaying games, the player is the central hero and their path to greatness is pre-determined. Take Skyrim, one of Morrowins successors, for example, you are the Dragonborn; there’s not much you can do about it yourself. In contrast: in Morrowind you just happen to confirm to a few elements of the Nerevarine prophecy (uncertain parentage, but certain birthsign), which isn’t all that special in itself. You are sent there with a purpose even unbeknownst to yourself to learn about the prophecies en see what’s what. These legends, stories and prophecies turn out to conflict one another, with parts of it only preserved in an oral tradition while other texts are being surpressed by the Temple authorities. As you go further along the path, you learn that you’re not the first or only Nerevarine-pretender. Many have gone before, all have been persecuted, all have ultimately failed. In the end, you never become the Nerevarine, but different factions start to recognize you as such, ending in official recognition by the Tribunal Temple and Vivec himself, who rescinds the order of persecution. It’s an interesting reflection on how prophecies function and one of the few games that take such an approach to being a hero.

Besides the role of prophecy, there is a huge and rich background lore. The history of Vvardenfell and Morrowind alone compromises quite a bit of (in-game) books and texts, about the Velothi exodus, the wars between the Chimer (the ancestors of the Dunmer) and the Dwemer, the invasion and subsequent repelling of the Nord invasion by an alliance between the Chimer leader Nerevar and the Dwemer king Dumac, how a dispute about occult magic on the Heart of Lorkhan lead to open war again, about the sudden disappearance of the whole Dwemer race in the midst of the Battle of Red Mountain and the different interpretations of the treason by the Tribunal, where Nerevar was killed, Dagoth Ur got banished and the Tribunal made themselves living gods. But also later historical events, that are (tellingly) ignored by many Dunmer themselves, such as the invasion and annexation by the Empire of the Septims, with Vvardenfell as a Temple reserve with its own law, or it’s later opening up to outsider development (a mere 13 years before the events of the game itself).

This special nature of the Vvardenfell Temple administration leads to some discrepancies with established custom on the Imperial mainland, such as slavery being legal and a more permissive stance towards necromancy - a huge aspects of Dunmer culture involves ancestor worship and involves summoning ghosts of said ancestors in necromantic rituals. All of these make for a highly unique mix, even inside the lands of Tamriel. There are some other regions that have similar strange customs and possibilities. Unfortunately the developers haven’t chosen these for their sequels (yet) and have instead opted for more traditional settings such as the Imperial province of Cyrodill and the Nord lands of Skyrim. One can only hope that a future visit to Elsweyr or Black Marsh get the unique treatment they deserve.

Tribunal & Bloodmoon

Morrowind was followed up with two expansions: Tribunal in the same year en Bloodmoon in 2003, rather quick given that there were numerous problems with the base game upon release (not that I know much about it, I wouldn’t play it for a few more years, as I was only twelve at the time).

Tribunal is a bit of a mixed bag. The City of Mournhold feels empty. Even though the architecture is interesting, the vast spaces are sparsely populated with almost nothing to do, besides the main questline. The dungeons are interesting though, the idea of ‘lost underground city’, haunted catacombs and antediluvian Dwemer ruins are engaging and impressive.

Although I’ve played Morrowind quite a lot, completing the main quest, explorer the world time and again, I never ventured into the Bloodmoon expansion before, except for a short trip to Fort Frostmoth and a quick return trip. So this playthrough was the first time exploring the snowy forests and defiling its ancient barrows. While the expansion is well rounded in itself, the isle of Solstheim just isn’t that interesting as the rest of Morrowind. It’s in effect a premonition of the later games that step back from weird, original world-building and a move towards more traditional fantasy settings, in this case the viking-like Nords.

Playing in 2020

More than 17 years after its release, the game still inspires people. A huge community of fans keeps making art and mods for the game. The Tamriel Rebuilt project has been working the extended Morrowind province (in contrast to just the island of Vvardenfell in the original game) for two decades. Seperate mods are being released daily and there is a team working on a full remake of the game in the newer Skyrim engine, called Skywind. Another big project is OpenMW, a new engine for the game that runs on modern hardware, multiple operating systems and adds native support for many new technologies. There’s even a musician called Young Scrolls making music inspired by Morrowind: definitely check out Balmora Vice or Dagothwave!

I reinstalled the game and did another playthrough during the covid-19 crisis and wrote this piece. I used the Morrowind Graphics Guide and Thasthus' guide as a basis and learned to work with Wrye Mash to install and manage the huge amount of mods.

One thing I wonder is how will all this change by 2030? Or 2040? Will this game reach a certain status enjoyed by some movies or other artwork? Will it still be playable, the community alive? Will we recognize the modders work as being a vital part and even some sort of digital archeology for keeping the old game alive, both by updating it for contemporary use or by remaking it? But also: will I still play it? And will I still find something new to appreciate that I didn’t before?